punters vs. society, an illustrated guide

15 February 2016, 12:01

brownie snaps

Below, we see the users of a product—e.g. a piece of software, an (internet) service, a device:

All users are different. Above we see the diversity of this user society depicted in two dimensions; no two are in the same spot. In reality this spread happens in dozens of dimensions. Even for very specialised user groups like ‘font designers for indochinese languages,’ there is plenty of diversity in many dimensions.

We all act like selfish punters; you, me, everyone. And when we are individually engaged in talk about a product, we will offer self‐centred opinions on what matters most and self-serving feature requests, i.e. our wants:

The dynamic we see illustrated above is very common in the software industry. You will find it in 99% of—

- custom software projects for companies, NGOs or the government, during requirements gathering;

- small and medium‐sized software companies where the boss, sales, support and/or consultants talk to customers and users;

- any kind of user forum, online or otherwise;

- take (a variant of) the second point above and combine it with the third, that’s F/LOSS, all of it;

- anywhere where market research is deployed.

write write, scribble scribble

It is also very common in the software industry to earnestly administrate user wants:

Common forms of this are—

- lists of use cases;

- use cases in sheep’s clothing: user stories;

- bug trackers; not necessarily as an enhancement or a feature request, it may be dressed up as a bug, or a usability problem;

- feature roadmaps;

- a lingering pressure, guilt, or fear in the minds of those in charge—boss, product manager, or maintainer;

- a consensus among (part of) the crew: ‘people keep asking for XYZ, we could hack something basic in a couple of days’ (yeah sure).

Now we can compare this administration of wants to the user society:

We see that at best, wants are good at describing the fringe of the society, but 80% of them are downright far‑out and esoteric.

Since wants are so overwhelmingly used in the industry to drive products and projects, there is overwhelming evidence that this leads to awful results. It is completely normal that a majority of time and talent is spent on adding far‑out and esoteric features that are instant bloat.

And thus everybody loses: makers, users and financial backers.

doing it right

Now we are going to stop flirting with disaster.

User research avoids all what has been described up to now in this post. The focus is on—

- finding out what users need;

- quality and depth of these findings;

- understanding the mechanisms at play.

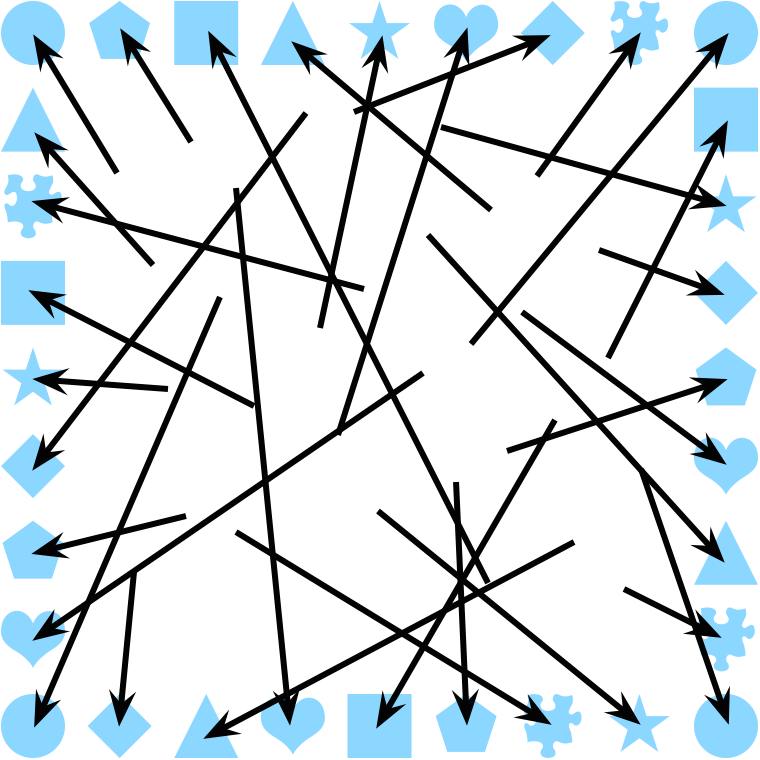

Instead of listening to everbody and their dog, researchers accompany a selection of representative participants on a ‘journey‘ through the pertaining activity, while constantly picking their brain:

Above, we see depicted that when users still insist on pushing their wants (i.e. go far out), researchers reel them in by questioning; peeling away layers of rationalisation in order to understand the underlying needs.

These needs are not exotic, they are basic human needs (e.g. control, overview, feedback, organisation, a stable environment, a simple rule book) that form the center of the picture—and are central to making it work for users.

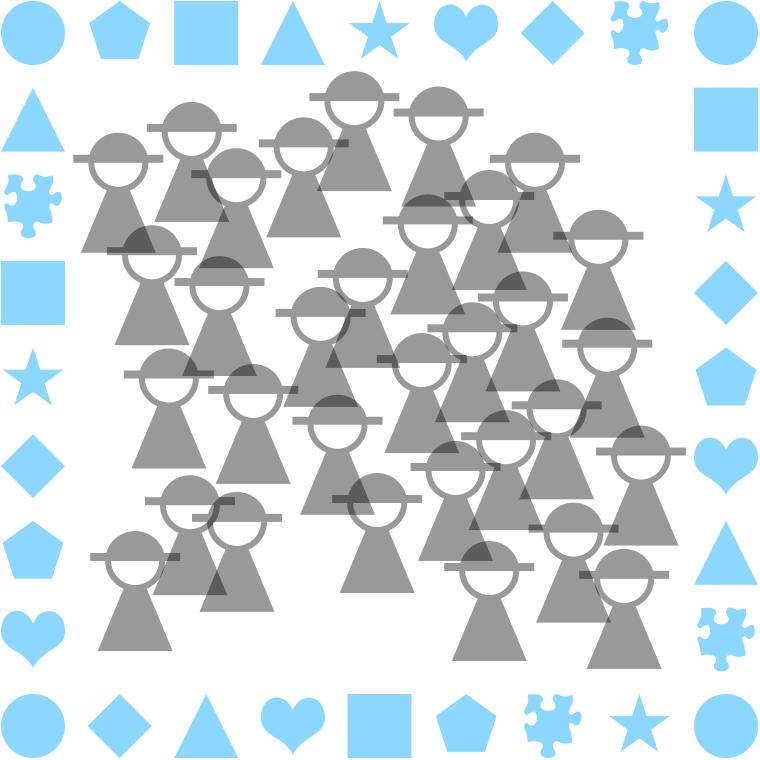

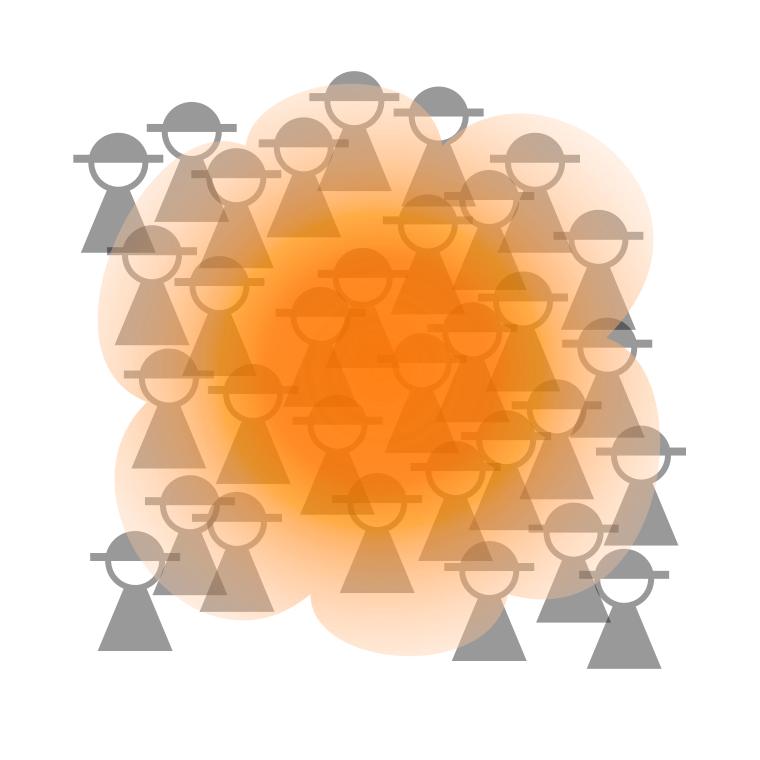

Researchers and designers collaborate on constructing a model—an understanding—of the user society. The centre of the picture is where one finds the commonalities in the (analysed) research material:

This is the heart of the matter. It is surrounded by the diversity in needs as found by the research. Note that there is a hard edge to this model: what is outside is certainly out of scope.

The qualitative aspect of research (e.g. taking into account the tone of voice or facial expression when something is stated) makes a world of difference. It is this richness of information that makes user research so effective. We see above that some outliers have been ignored in the user model. This is done with full confidence, based on the research.

core, non‑core

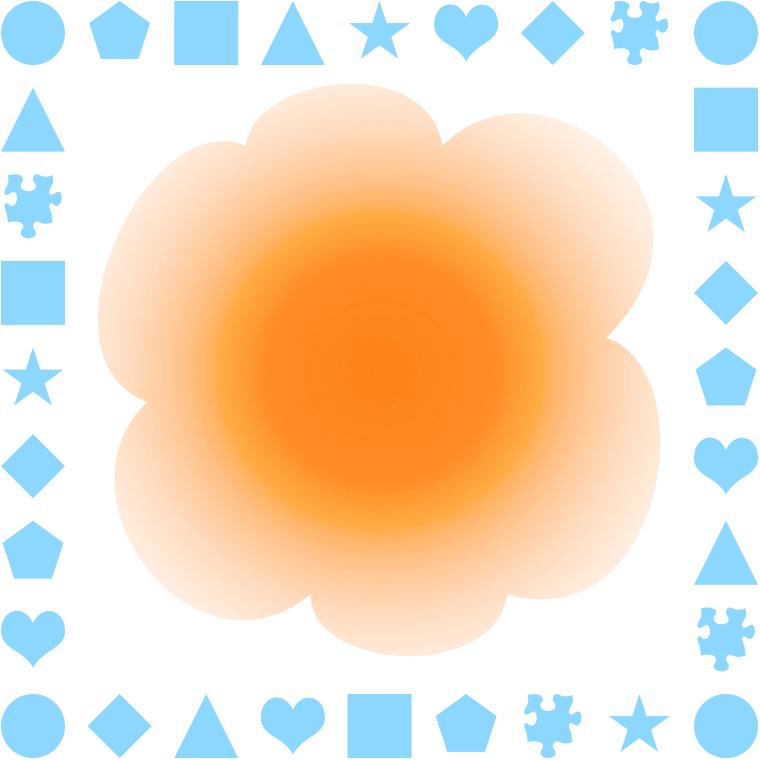

Now we can compare the needs‐based user model to the user society:

The coverage of the model works out so well, that it is difficult to see the actual users. This is especially true for the heart of the matter. Note that some users at the very fringe of society may feel left out; they are covered a little bit or not at all.

In a design‐driven approach, the needs‐based user model is used to decide which features to add (cover the diversity, but nothing beyond the edge) and where to focus design and development effort (on the heart of the matter).

A/B testing

Zooming out, we now can compare the two approaches:

When compared to the results of user research, the bog standard, wildly popular method of listening to users and their wants—

- fails to record the heart of the matter;

- fails to record the diversity of user needs;

- is a list of disparate wishes, instead of a coherent, nuanced insight;

- highlights the fringe, the far‑out, the esoteric;

- gets you completely the wrong picture.

postscript

This past semester I discussed all this with my students at the BTK design school. To get the point across about the dangers of talking to users, I asked them ‘do you remember these creatures in mythology that always give you the wrong answer, so that you get lost?’

‘Yeah’, they said, ‘they are called trolls.’

Labels: fundamental, product phase, top story, war and peace

war and peace—the 5th column

21 August 2015, 10:22

cuckoo

Last week my friend Jan‑C. Borchardt tweeted:

‘Stop saying »the user« and referring to them as »he«. Thanks!’

To which I replied:

‘“They”; it is always a group, a diverse group.

‘But I agree, someone talking about “the user” is a tell‐tale sign that they are part of the problem, not the solution.’

All that points at a dichotomy that I meant to blog about for a long time. You see, part one of the war and peace series looked at all four parties involved—product makers, users, developers and designers—as separate silos. The logical follow‑up is to look at hybrid actors: the user‐developer, the product maker‐developer, et cetera.

While working to provide a theoretical underpinning to 20+ years of observation of performance in practice of these hybrid actors, I noticed that for all user‐XYZ hybrids, the user component has not much in common with the users of said product. In general, individual users are in conflict with the user group they are part of.

That merits its own blog post, and here we are.

spy vs. spy

First we got to get away from calling this ‘user versus users.’ The naming of the two needs to be much more dissimilar, both to get the point across and so that you don’t have to read the rest of this post with a magnifying glass, just to be sure which one I am talking about.

During the last months I have been working with the concept of inhabitants vs. their city. The inhabitants stand for individual users, each pursuing their personal interests. All of them are united in the city they have chosen to live in—think photoshop city, gmail city, etc. Each city stands for a bustling, diverse user group.

inner city blues

With this inhabitants & city model, it becomes easier to illustrate the mechanisms of conflict. Let’s start off with a real‐life example.

Over the next years, Berlin needs to build tens of thousands units of affordable housing to alleviate a rising shortage. Because the tens of thousands that annually move to Berlin are (predominantly) looking for its bubbly, relaxed, urban lifestyle, building tower blocks on the edge of town (the modernist dream), or rows of cookie‐cutter houses in suburbia (the anglo‐saxon dream) won’t solve anything.

What is needed is development of affordable housing in the large urban area of Berlin. A solid majority of the population of Berlin agrees with this. Under one condition: no new buildings in their backyard. And thus almost nothing affordable gets built.

What can we learn from this? Naturally reactionary inhabitants take angry action to hinder the development that their city really needs. I am sure this rings a bell for many a product maker.

yee‑haw!

The second example is completely fictional. A small posse of inhabitants forms and petitions the city to build something for their (quite) special interest: a line‐dancing facility. At first they demand that the city pays for everything and performs all the work. When this falls on deaf ears, the posse organises a kickstarter where about 150 backers chip in to secure the financing of the building work.

Being petitioned again, the city asks where this line‐dancing facility could be located. The posse responds that in one of the nicest neighbourhoods there is a empty piece of grassland. The most accessible part of it would be a good location for the facility and its parking lot.

The city responds that this empty grassland host events and community activities on about 100 days a year, many of which are visited by folks from all over the city. And all other days of the year the grassland serves the neighbourhood, simply by being empty and semi‐wild nature; providing a breather between all the dense and busy urbanisation, and a playground for kids.

repeat after me: yee‑haw!

This angers the line‐dancing posse. They belittle the events and activities, and don’t know anyone who partakes in them. The events can be moved elsewhere. The land just sits there, being empty, and is up for grabs. Here they are with a sack of money and a great idea, so let’s get a move on.

The city then mentions one of its satellite towns, reachable by an expressway. At its edge, there is plenty of open space for expansion. It would be good to talk to the mayor of that town. The posse is now furious. Their line‐dancing facility, which would make such a fine feature for the heart of the city, being relegated to being an appendix of a peripheral module? Impossible!

What can we learn from this? Inhabitants will loudly push their special‐interest ideas, oblivious to the negative impact on their city. Again this must also ring a bell for many product makers.

leaving the city

Now that the inhabitants & city model has helped us to find these mechanisms, I must admit there are also some disadvantages to it. First, cities do not scale up or down like user groups do. I have worked on projects ranging from a handful of users (hamlet) to 100 million (large country). And yes, the mechanisms hold over this range.

Second, I suspect that many, especially those of a technological persuasion, will take the difference between inhabitants and their city to be that the former are the people, and the latter the physical manifestation, especially buildings and infrastructure.

no escape

Thus we move on for a second time, picking a more generic route, but one with attitude. For individual users I have picked the term punter. If that smacks to you as clientèle that is highly opinionated, with a rather parochial view of their environs, then you got my point.

Now you may think ‘is he picking on certain people?’ No, on the contrary: we all are punters, for everything we use: software, devices, websites, services—hell, all products. You, me, everyone. We are all just waffling in a self‐centred way.

There is no single exception to the punter principle, even for people whose job is centred on getting beyond the punter talk and to the heart of the matter. It is simply a force of nature. The moment we touch, or talk about, a product we use, we are a punter.

greater good

For the user group I have picked the term society. This works both as a bustling, diverse populace and as a club of people with common interests (the photoshop society, gmail society, product‑XYZ society). Some of you, especially when active in F/LOSS, will say ‘is not community the perfect term here?’ It would be, if it wasn’t already squatted.

After almost a decade in F/LOSS I can say that in practice, ‘community’ boils down to a pub full of punters (i.e. chats, mailing lists and forums). In those pubs you will hear punters yapping about their pet feature (line dancing) and loudly resisting structural change in their backyard. What you won’t hear is a civilised, big‐picture discourse about how to advance their society.

it differs

One thing that last week’s exchange with Jan‑C., and also a follow up elsewhere, brought me is the focus on the diversity of a (product) society. This word wonderfully captures how in dozens and dozens of dimensions people of a society are different, have different needs and different approaches to get stuff done.

I can now review my work over the last decade and see that diversity is a big factor in making designing for users so demanding. The challenge is to create a compact system that is flexible enough to serve a diverse society (hint: use the common interests to avoid creating a sprawling mess).

I can also think of the hundreds of collaborators I worked with and now see what they saw: diversity was either ‘invisible,’ in their mono‐cultural environment, or it was such an overwhelming problem that they did not dare tackle it (‘let’s see what the user asks for’). Talking about ‘the user’ is the tell‐tale sign of a diversity problem.

The big picture emerges—

If you want to know why technology serves society so badly, look no further than the tech industry’s problem to acknowledge, and adapt to, the diversity of society.

Yes, I can see how the tendency of the tech sector to make products that

only its engineers understand has the same roots as the now widely publicised

problem that this sector has a hard time being inclusive to anyone who is not

a male,

but why?

Back to the punters. That we all act like one was described ages ago by the tragedy of the commons. This is—

‘[…] individuals acting independently and rationally according to each’s self‐interest behave contrary to the best interests of the whole group by depleting some common resource.’

If you think about it for a minute, you can come up with many, many examples individuals acting like that, at the cost of society. The media are filled with it, every day.

what a waste

What common resources do punters strive to deplete in (software) products? From my position that is easy to answer—

- makers’ time; both in proprietary and F/LOSS, the available time of the product maker, the designer and developers is scarce; it is not a question of money, nor can you simply throw more people at it—larger teams simply take longer to deliver more mediocre results. To make better products, all makers need to be focussed on what can advance their society; any time spent on punter talk, or acts (e.g. a punter’s pull request), is wasted time.

- interaction bandwidth; this is, loosely, a combination of UI output (screen space, sound and tactile output over time) and input (events from buttons, wheels, gestures), throttled by the limit what humans can process at any given time. Features need interaction and this eats the available bandwidth, fast. In good products, the interaction bandwidth is allocated to serve its whole society, instead of a smattering of punters.

The tragedy of (software) products is that it’s completely normal that in reaction to punters’ disinformation and acts of sabotage, a majority of maker’s time and a majority of interaction bandwidth gets wasted.

Acts of sabotage? SME software makers of specialised tools know all about fat contracts coming with a list of punter wishes. Even in F/LOSS, adoption by a large organisation can come with strings attached. Modern methods are trojan horses of punter‐initiated bounties, crowdfunding or code contributions of their wishes.

the point

This makes punters the fifth column in the UI version of war and peace. Up to now we had four players in our saga—product maker, users (i.e. the society), developers and the designer—and here is a fifth: a trait in all of us within society to say and do exactly that what makes (software) products bloated, useless, collapse under their own weight and burn to the ground.

It is easy to see that punters are the enemy of society and of product makers (i.e. those who aim to make something really valuable for society). Punters have an ally in developers, who love listening to punters and then build their wishes. It makes the both of them feel real warm and fuzzy. (I am still not decided on whether this is deliberate on the part of developers, or that they are expertly duped by punters offering warmth and fuzziness.)

That leaves designers; do they fight punters like dragon slayers? No, not at all. Read on.

the dragon whisperer

Remember that punters and society are one and the same thing. The trick is to attenuate the influence of punters to zero; and to tune into the diversity and needs of society and act upon them. Problem is, you only get to talk to punters. Every member of society acts like a punter when they open their mouth.

There is a craft that delivers insight into a society, from working with punters. It is called user research. There are specialist practitioners (user researchers) and furthermore any designer worth their salt practices this. There is a variety of user research methods, starting with interviewing and surveying, followed up by continuous analysis by the designer of all punter/society input (e.g. of all that ‘community’ pub talk).

the billion‐neuron connection

What designers do is maintain a model of the diversity and needs of the society they are designing for, from the first to the last minute they are on a project. They use this model while solving the product‐users‐tech puzzle, i.e. while designing.

When the designer is separated from the project (tech folks tend towards that, it’s a diversity thing) then the model is lost. And so is the project.

(Obligatory health & safety notice: market research has nothing to do with user research, it is not even a little bit useful in this context.)

brake, brake

At this point I would like to review the conflicts and relationships that we saw in part one of war and peace, using the insights we won today. But this blog post is already long enough, so that will have to wait for another day.

Instead, here is the short, sharp summary of this post:

- Users groups can be looked at in two ways: as a congregation of punters and as a society.

- We all are punters, talking in a in a self‐centred way and acting in our self‐interest.

- We are also all members of (product) societies; bustling, diverse populaces and clubs of people with common interests (the photoshop society, gmail society, product‑XYZ society).

- Naturally reactionary punters take angry action to hinder structural product development.

- Punters will loudly push their special‐interest ideas, oblivious to the negative impact on their society.

- The diversity of societies poses one of the main challenges in designing for users.

- The inability of the tech sector to acknowledge, and adapt to, the diversity of society explains why it tends to produce horrible, tech‐centric products.

- In a fine example of ‘the tragedy of the commons,’ punters behave contrary to the best interests of their society by depleting makers’ time and interaction bandwidth.

- Punters act like a fifth column in the tri‑party conflict between product makers, society and developers.

- You only get to talk to punters, but pros use user research methods to gain insight into the diversity and needs of a society.

- Everyone gets bamboozled by punters, but not designers. They use user research and maintain a model of diversity and needs, to design for society.

Interested, or irritated? Then (re)read the whole post before commenting. Meanwhile you can look forward to part three of war and peace, the UI version.

Labels: design stage, fundamental, top story, war and peace

war and peace, the abridged UI version

18 October 2013, 16:47

Actually, I intend this blog post to be shorter than usual.

peace

I like to think that my work as an interaction architect makes the world a better place.

I realise product makers’ dreams, designing elegant and captivating embodiments they can ship. I save terminally ill software and websites from usability implosion, and in the meantime get their makers a lot closer to what they always intended.

On top of that, I provide larger organisations with instruments to reign in the wishful thinking that naturally accumulates there, and to institute QA every step along the way.

All of this is accomplished by harmonising the needs of product makers, developers and users. You would think that because I deliver success; solutions to fiendishly complex problems; certainty of what needs to be done; and (finally!) usable software, working with these three groups is a harmonious, enthusiastic and warm experience.

Well, so would I, but this is not always the case.

war

The animosity has always baffled me. I also took it personally: there I was, showing them the light at the end of the tunnel of their own misery, and they get all antsy, hostile and hurt about it.

After talking it through with some trusted friends, I have now a whole new perspective on the matter. Sure enough, as an interaction architect I am always working in a conflict zone, but it is not my conflict. Instead, it is the tri‑party conflict between product makers, developers and users.

- The main conflict between product makers and users

- Each individual user expects software and websites really to be made for me‐me‐me, while product makers try to make it for as many users as possible. Both are a form of greed.

- There is also a secondary conflict, when users ‘pay’ the product maker in the form of personal, behavioural data, and/or by eyeballing advertisements—’nuff said.

- The main conflict between product makers and developers

- Product makers want the whole thing perfectly finished by tomorrow, while reserving the right to change their mind, any given minute, on what this thing is. Developers like to know exactly up front what all the modules are they have to build—but not too exactly, it robs the chance to splice in a cheaper substitute—while knowing it takes time, four times more than one would think, to build software.

- That this is a fundamental conflict is proven by the current fad for agile development, where it is conveniently forgotten that there is such a thing as coherence and wholeness to a fine piece of software.

- The main conflict between developers and users

- This one is very simple: who is going to do the work? Developers think it is enough to get the technology running on the processing platform—with not too many crashing bugs—and users are free to do the rest. Users will have no truck with technology; they want refined solutions that ‘just work™,’ i.e. the developers do the work.

All of this makes me Jimmy Carter at Camp David. The interaction design process, the resulting interaction design and its implementation are geared towards bringing peace and prosperity to the three parties involved. This implies compromises from each party. And for me to tell them things they do not like to hear.

- Product makers need to be told

- to make real hard choices and define their target user groups narrowly—it is not for everyone;

- that they cannot play fast and loose with users’ data;

- to take the long, strategic view on the product level, instead of trying to micro‐manage every detail of its realisation;

- to concentrate on the features that really make the product, instead of a pile‑up of everybody’s wish lists;

- to accept that they cannot have it all, and certainly not with little effort and investment.

- Users need to be told that

- each of them are just part of a (very large) group and that in general the needs of this group are addressed by the product;

- using software and websites takes a certain amount of investment from them: time, money, participation and/or privacy;

- software cannot read their minds; to use it they will need to input rather exactly what they are trying to achieve;

- quite a few of them are outside the target user group and their needs will not be taken into consideration.

- Developers need to be told

- that we are here to make products, not just code modules;

- no substitutes please, the qualities of what needs to be built determines success;

- users cannot be directly exposed to technology; an opaque—user—interface is needed between the two;

- if it isn’t usable, it does not work.

No wonder everybody gets upset.

peace

How do I get myself some peace? Well, the only way is to obtain a bird’s‐eye view of the situation and to accept it.

First, I must accept that this war is inherent to any design process and all designers are confronted by it. Nobody ever really told us, but we are there to bring peace and success.

Second, I have to accept that product makers, developers and users get upset with my interaction design solutions for the simple reason that they are now confronted with the needs of the other two parties. They had it ‘all figured out’ and now this turns up. (Yes, I do also check if they have a point and discovered a bug in my design.)

Third, I have to see my role as translator in a different light. We all know that product makers, developers and users have a hard time talking to each other, and it is the role of the interaction architect to translate between them.

It is now clear to me that when I talk to one of the parties involved, I do not only fit the conversation to their frame of reference and speak their language, but also represent the other two parties. There is some anger potential there: for my audience because I speak in such familiar terms, about unfamiliar things that bring unwelcome complexity; for me because tailored vocabulary and examples do not increase acceptance from their side.

Accepting the war and peace situation is step one, doing something about it is next. I think it will take some kind of aikido move; a master blend of force and invisibility.

Force, because I am still implicitly engaged to bring peace and success, and to solve a myriad of interaction problems nobody wants to touch. This must be met head‑on, without fear.

Invisibility, because during the whole process it must be clear to all three parties that they are not negotiating with me, but with each other.

postmortem

That is it for today, I promised to keep it short. There are some interesting kinks and complications in the framework I set up today, but dealing with them will have to wait for another blog post.

Labels: architects, fundamental, top story, war and peace

If you like to ask Peter one burning question and talk about it for ten minutes, then check out his available officehours.

What is Peter up to? See his /now page.

- info@mmiworks.net

- +49 (0)30 345 06 197

- imprint

Peter Sikking

Peter Sikking